Robert Rauschenberg Centennial

By Laura Heyrman

“My art is about paying attention - about the extremely dangerous possibility that you might be art.” – Robert Rauschenberg (American, 1925-2008)

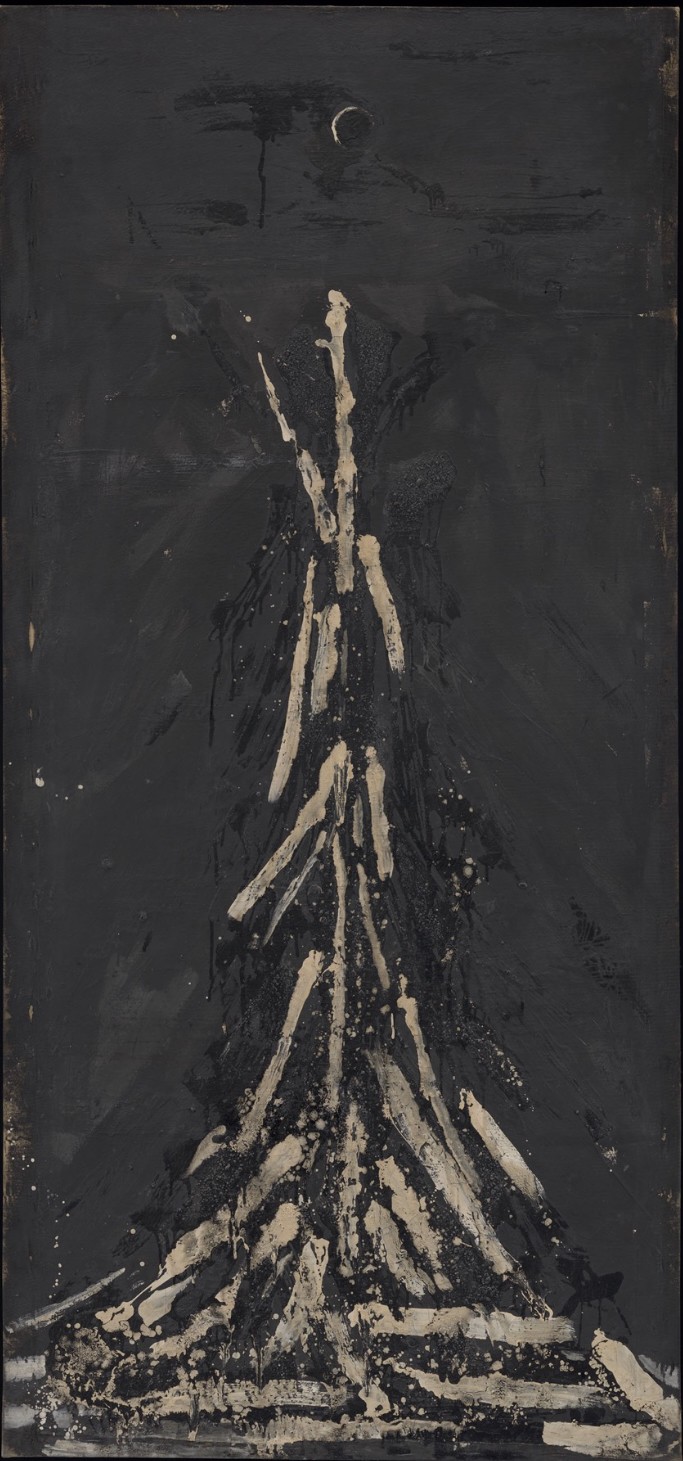

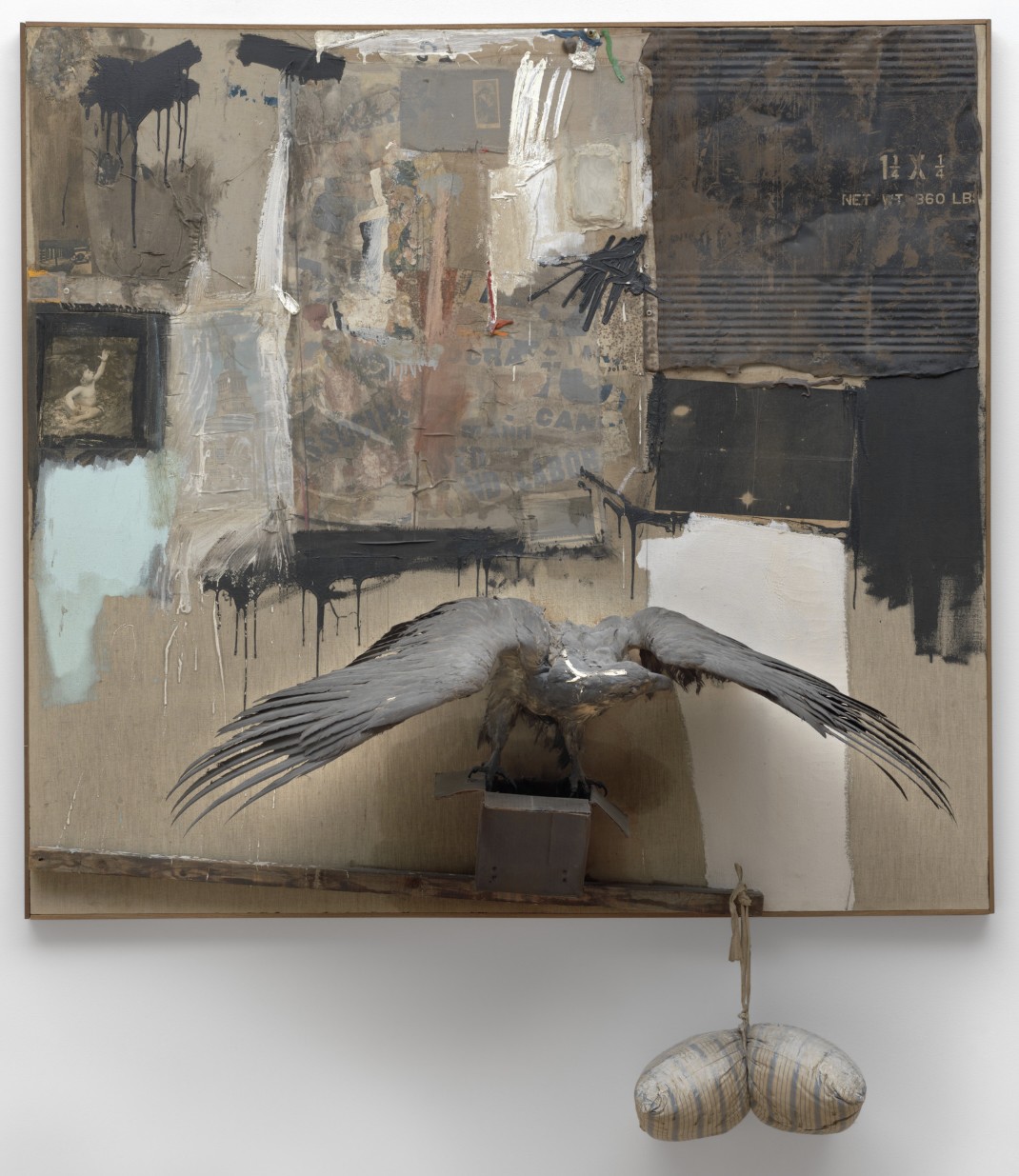

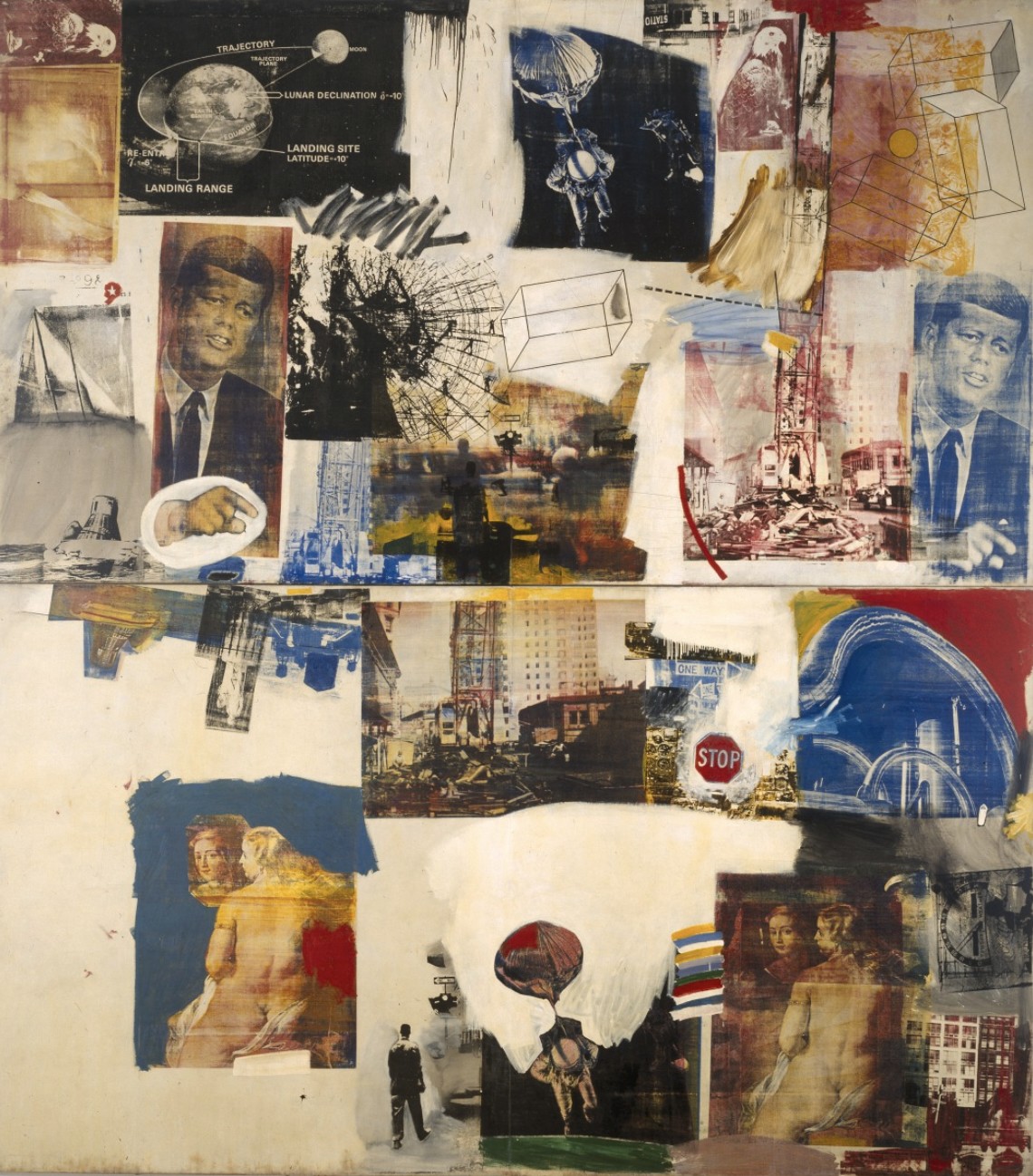

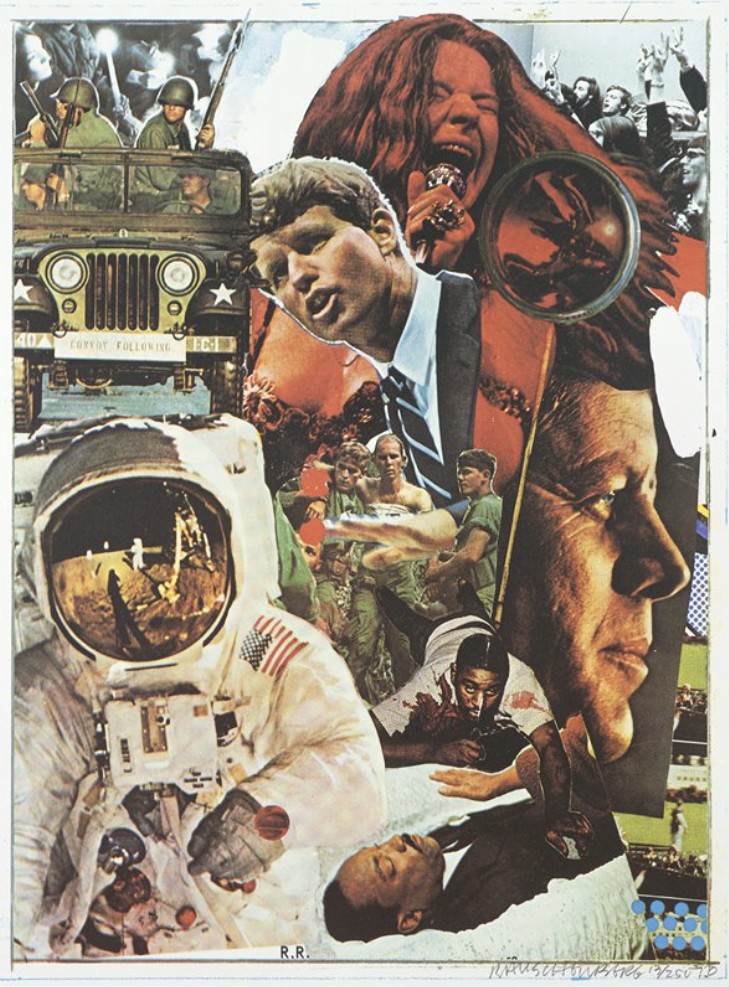

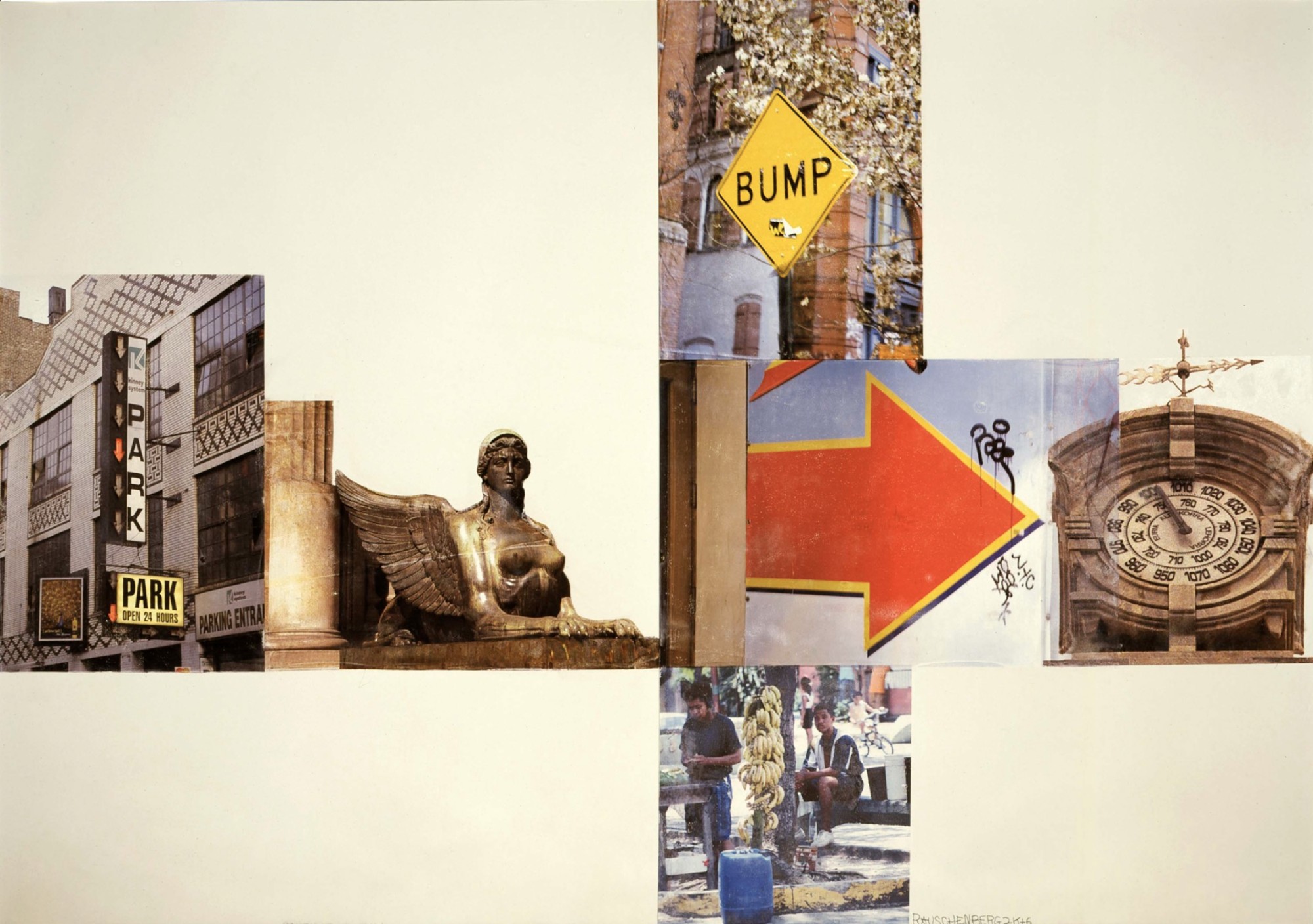

October 22, 2025 marks the centennial of Robert Rauschenberg’s birth. An artist who challenged the dominant Abstract Expressionist style (irequireart.substack.com/p/chance-encounters-edition-23) in the 1950s, Rauschenberg experimented with a wide variety of media: painting, sculpture, prints, photography, and performance, in order to make sense of the flood of images which characterizes modern life. Though he had many friendships and collaborators among his contemporaries, Rauschenberg remained creatively independent of all the movements and artists’ groups that developed during his lifetime. Nevertheless, his work shows his familiarity with earlier 20th century art movements like Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism. From Cubism, he drew the fragmentation of the picture plane, especially apparent in screen prints like Signs (1970) in this slide show. The artist’s belief that there is no distinction between real life and art had its origins in the Dada movement. Rauschenberg’s use of found objects is reminiscent of the readymades of Marcel Duchamp (French-American, 1887-1968), one of the foremost practitioners of Dada and Surrealism.

“I think a picture is more like the real world when it is made out of the real world.” – Robert Rauschenberg

Rauschenberg, like his friend and fellow artist Jasper Johns (American, b. 1930), is sometimes described as a Neo-Dada artist. In addition to his attitude about art and real life, he used traditional Dada techniques such as playfulness, iconoclasm, and appropriation (the use of images borrowed from sources like newspapers, magazines, and other art). In addition, characteristics of other styles contemporary with the artist’s career, can be found in Rauschenberg’s art. From Abstract Expressionism, Rauschenberg adopted expressive painterly passages. These can be seen in many of his works, especially Charlene (1954), Monogram (1958-1959), and Canyon (1959) in the slide show below. Critics in the 1960s and 1970s associated Rauschenberg’s use of mechanical reproduction and inclusion of familiar objects and people in his works with Pop Art.

“I don't think of myself as making art. I do what I do because I want to, because painting is the best way I've found to get along with myself.” – Robert Rauschenberg

Rauschenberg was christened Milton Ernest Rauschenberg when he was born in Port Arthur, Texas. He changed his first name to Robert in 1947 around the time he began his first formal studies to become an artist, at the Kansas City Art Institute. He would go on to study at the well-known art schools Black Mountain College and the Art Students League in the United States and the Académie Julian in France. Rauschenberg was never very successful as a student; his teachers weren’t supportive of his constant experimentation. Over time, though, the artist found a supportive community of artists, composers, and dancers, most notably visual artists Johns and Cy Twombly (American, 1928-2011), composer John Cage (American, 1912-1992), and dancer-choreographer Merce Cunningham (American, 1919-2009).

“I prefer images that are less specific, so there is room for everyone's imagination.” – Robert Rauschenberg

The art form for which Rauschenberg is best known are the Combines, works which blend sculptural and painted elements and break down the traditional divide between those two. The idea of mixing sculpted and painted elements had occurred to some earlier artists, especially within the Dada and Surrealism movements, but no other artist had focused so intently on developing the concept as Rauschenberg did between 1954 and 1964. The artist invented the name “Combine” for this format and by mixing found objects into painted and sculpted components, he gave ordinary objects broader significance by incorporating them into art.

“Anything you do will be an abuse of somebody else's aesthetics. I think you're born an artist or not. I couldn't have learned it.” – Robert Rauschenberg

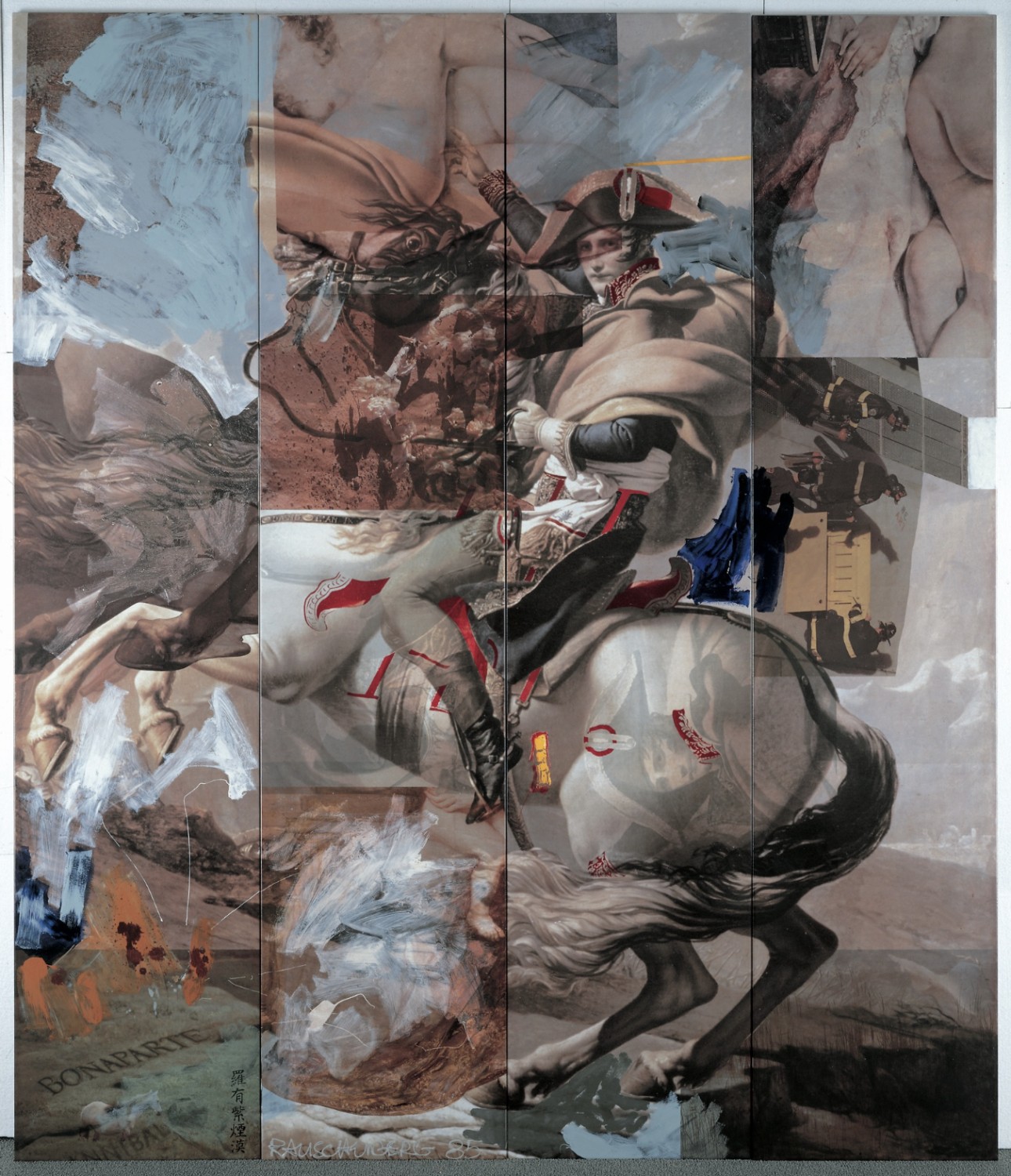

Rauschenberg’s art is marked by the recurrence of artistic practices and motifs throughout his career. Even during his student years, he introduced grid formats, doubling and mirroring of elements, and the use of sequences or progressions. In terms of motifs, body parts, modes of transportation, fine art reproductions, lettering, and diagrams appear early on and continue to draw the artist’s attention for the next sixty years. Rauschenberg’s career is also marked by collaborations. He frequently designed sets and costumes for Merce Cunningham’s troupe, but also for other dance companies. The artist was a frequent participant in performances of his own and others’ devising. In 1952, he was one of many to take part at Black Mountain in what some scholars consider the first Happening, an unscripted blend of music, poetry readings, dance, artistic creation, and theatrics. Rauschenberg also developed projects with printmakers, craftspeople, and engineers. Some of his Combines required engineering assistance for lighting, sound, and movement. Able Was I Ere I Saw Elba II (1985), one of the artist’s Japanese Recreational Clayworks series included in this slide show, is an example of Rauschenberg’s collaboration with craftspeople. Working with prefabricated clay plaques bearing reproductions of famous Western artworks made by the Otsuka Ohmi Ceramics Company in Shigaraki, Japan, the artist added images of contemporary Japan and other places from his own photographs along with gestural strokes of pigment.

“I put my trust in the materials that confront me, because they put me in touch with the unknown.” – Robert Rauschenberg

Though his early works provoked confusion or dismay among critics, in the 1960s, Rauschenberg experienced increasing success in the United States and abroad. In 1964, he was asked to contribute a work to the New York State Pavilion at the New York Word’s Fair; Skyway, an oil painting and silkscreen on canvas work, was the artist’s submission. In the same year, Rauschenberg was awarded the International Grand Prize at the 32nd Venice Biennale. In spite of his success, he remained interested in experimentation with materials and fascinated by incorporating found objects and images into his compositions. He explored cardboard, textiles and metals as supports for his works, as well as discovering traditional artforms in new locales as his work drew interest around the world. The artist made a point of arranging exhibitions in places where freedom of artistic expression had been suppressed.

“People ask me, 'Don't you ever run out of ideas?' Well, on the first place, I don't use ideas. Every time I have an idea, it's too limiting and usually turns out to be a disappointment. But I haven't run out of curiosity.” – Robert Rauschenberg

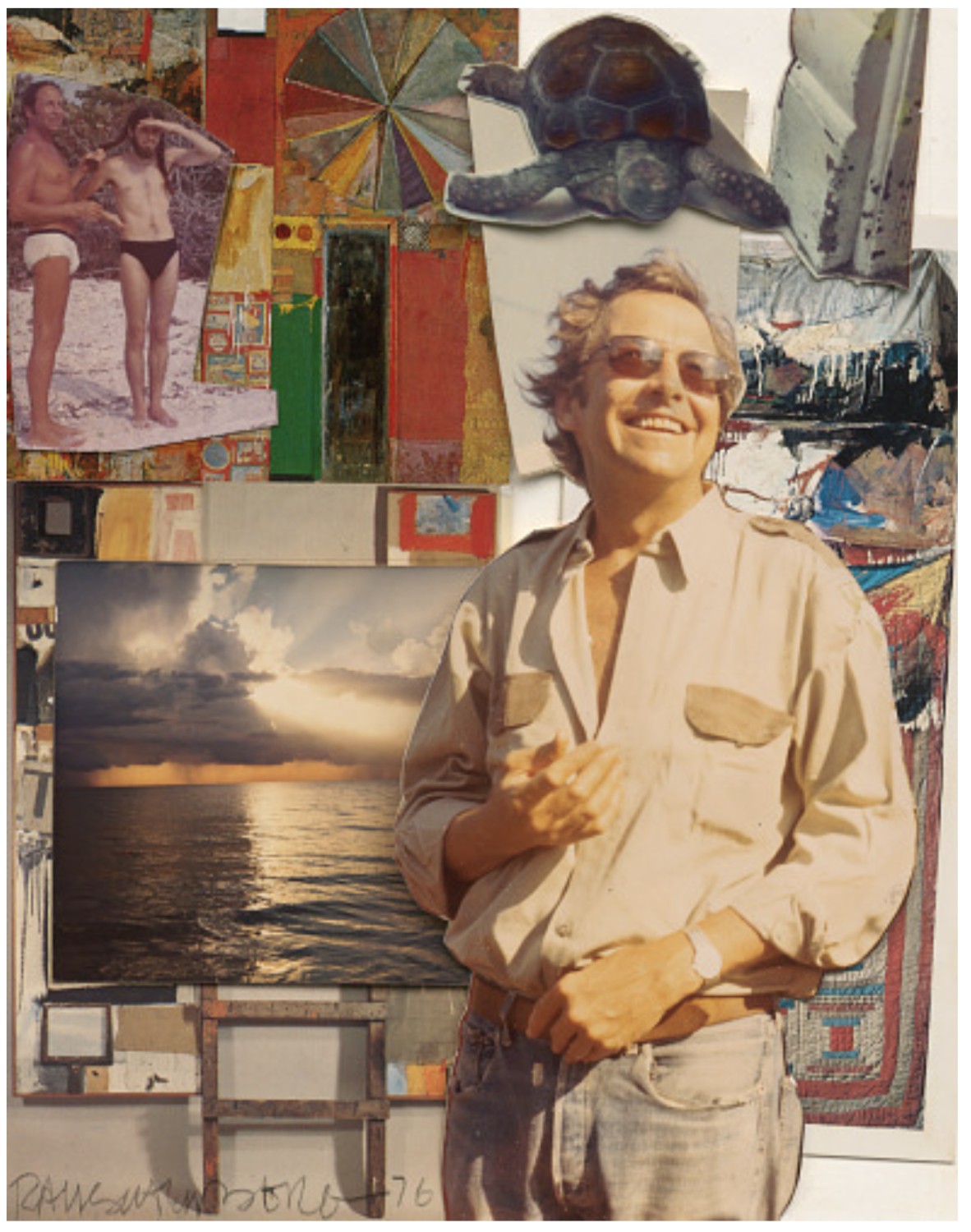

Rauschenberg’s long career meant that he had the opportunity to help organize two retrospective exhibitions, in 1976 and in 1997. Both exhibitions had the effect of reintroducing the artist to his own earlier works. In the 1970s and 80s, he returned to earlier experiments with image transfers and silkscreen, utilizing both frequently in new series of works. In the late 1990s and 2000s, Rauschenberg continued to experiment with materials, working with glass for the first time, but also reintroduced images he had used earlier in his career, giving his late works an autobiographical bent. In 2002, Rauschenberg suffered a stroke which limited his use of the right arm. The artist learned to use his left arm for many purposes and continued to collaborate with printmakers and performers and to contribute to ecological and humanitarian causes.

“The artist’s job is to be witness to his time in history.” – Robert Rauschenberg

In addition to his innovative, visually complex work, Rauschenberg’s techniques, style, and subject matter have been an influence on younger artists. One can find the breakdown of the barriers between painting and sculpture, the combination of photographic imagery with more expressive applications of color and paint, and the blending of popular culture with more personally meaningful imagery in the work of many artists of the late 20th and 21st century. Few artists have created such a diverse body of work in a multitude of media and disciplines as Robert Rauschenberg.

Current exhibitions:

Robert Rauschenberg and the Flatbed Picture Plane, through December 31, 2025, at Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska, 12th and R Streets, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA. sheldonartmuseum.org/rauschenberg-flatbed-picture-plane

Five Friends: John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, through January11, 2026, at Museum Ludwig, Heinrich-Böll-Platz, 50667, Cologne/Köln, Germany. museum-ludwig.de/en/home/exhibitions/five-friends-john-cage-merce-cunningham-jasper-johns-robert-rauschenberg-cy-twombly

Robert Rauschenberg: Fabric Works of the 1970s, through March 1, 2026, at The Menil Collection, 1533 Sul Ross Street, Houston, Texas, USA. menil.org/exhibition/robert-rauschenberg-fabric-works-of-the-1970s

Robert Rauschenberg’s New York: Pictures from the Real World, through April 19, 2026, at the Museum of the City of New York, 1220 Fifth Avenue at 103rd Street, New York, New York, USA. mcny.org/exhibition/robert-rauschenbergs-new-york-pictures-real-world-0

Collection In Focus l Robert Rauschenberg: Life Can’t Be Stopped, through May 3, 2026, at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue at 88th Street, New York, New York, USA. guggenheim.org/exhibition/collection-in-focus-robert-rauschenberg-life-cant-be-stopped

Trisha Brown and Robert Rauschenberg: Glacial Decoy, through May 24, 2026, at Walker Art Center, 725 Vineland Place, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA. “Throughout November 2025, the program Rauschenberg@100: Merce Cunningham, Trisha Brown, Kyle Abraham will highlight the artistic lineage between its three titular choreographer-dancers and their partnerships with the artist. The series will include live performances and a Walker residency with the Trisha Brown Dance Company.” walkerart.org/calendar/2025/trisha-brown-and-robert-rauschenberg-glacial-decoy

Robert Rauschenberg and Asia, opening November 22, 2025, at M+, 38 Museum Drive, West Kowloon, Hong Kong. mplus.org.hk/en/exhibitions/robert-rauschenberg-and-asia

Please share your comments and questions on Substack. irequireart.substack.com/p/viewing-room-43/comments

Longer captions may not be fully visible on smaller screens. We apologize for the inconvenience.

If the caption obscures part of the artwork, click on the image to turn off the caption.