M. C. Escher: Realities

Few viewers can resist exploring the visual puzzles and illusions inherent in the prints of Maurits Cornelis Escher (Dutch, 1898 – 1972). Escher’s works have had international popularity for decades, beginning at least with the publication of some of his art in the April 1966 “Mathematical Puzzles” column in the magazine Scientific American. In spite of this popular acclaim, the artist received little attention from the art world during his lifetime. His first retrospective exhibition, held in the Netherlands, was held when he was 70, at the same time that Escher retired from publishing his work. He died two years later.

Understanding why M. C. Escher and his works were disregarded by the art world is difficult. During his lifetime there were artistic movements and individual artists who might have appreciated his ideas and images. These include De Stijl, founded in 1917 by Piet Mondrian (Dutch, 1872 – 1944) and Theo van Doesburg (Dutch, 1883 – 1931); Surrealism, especially as practiced by René Magritte (Belgian, 1898 – 1967); and the Op Art movement, active in the 1960s and 70s. The art world may have considered his work too mechanical and craftsman-like. Escher himself may have been partly responsible, as it appears that he made no effort to enter the art world. His training at the Technical College of Delft and the Haarlem School of Architecture and Decorative Arts may have affected his view of his works as “applied art” or “decorative art,” long viewed as second class art. Fortunately, in the contemporary era, such old-fashioned prejudices have begun to fall away and Escher’s work can be enjoyed in museums and galleries around the world.

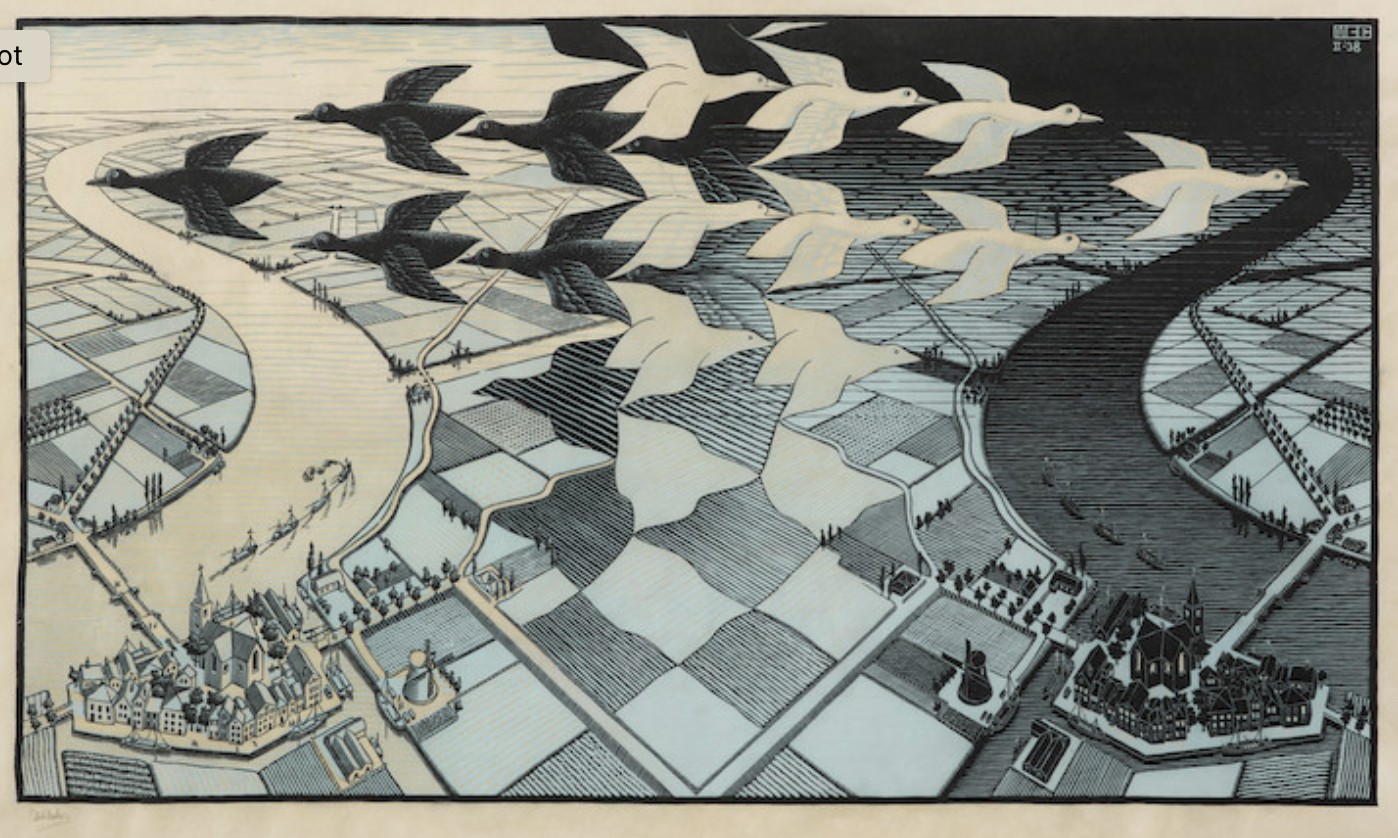

Though Escher thought of himself as lacking mathematical ability, his works drew the interest and enthusiasm of prominent mathematicians and crystallographers. His research and practice with tessellation (interlocking repeated patterns) has drawn praise from mathematicians. For Escher, tessellation verged on an obsession. He said: "It remains an extremely absorbing activity, a real mania to which I have become addicted, and from which I sometimes find it hard to tear myself away."

In addition to his interest in tessellation, represented in the slideshow by Day and Night (Blue Variant), Escher explored other mathematical and geometric concepts throughout his career, such as single point linear perspective, symmetry, and the depiction of polyhedra, that is, three dimensional solids with many planes, usually 6 or more. Escher is also well known for his images containing optical illusions based on impossible objects, that is, two dimensional images that are convincingly three dimensional to a viewer but could not actually exist as a physical three dimensional objects. Channels carrying water in Waterfall demonstrate this illusion.

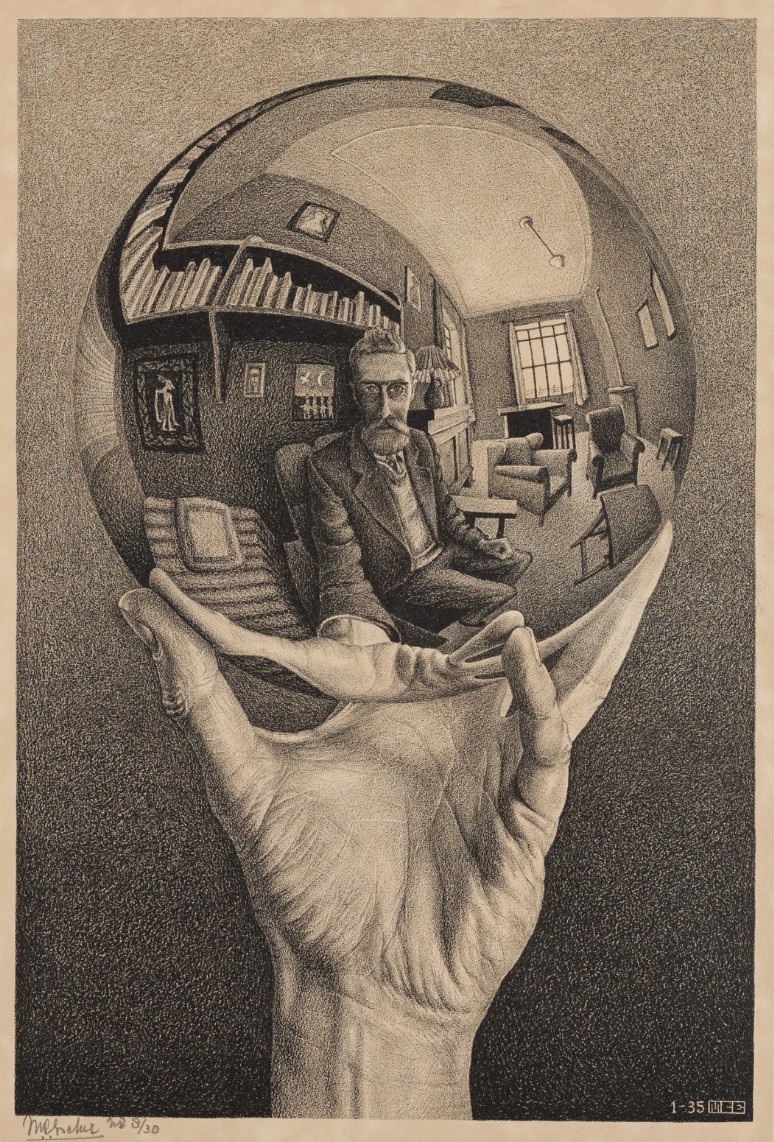

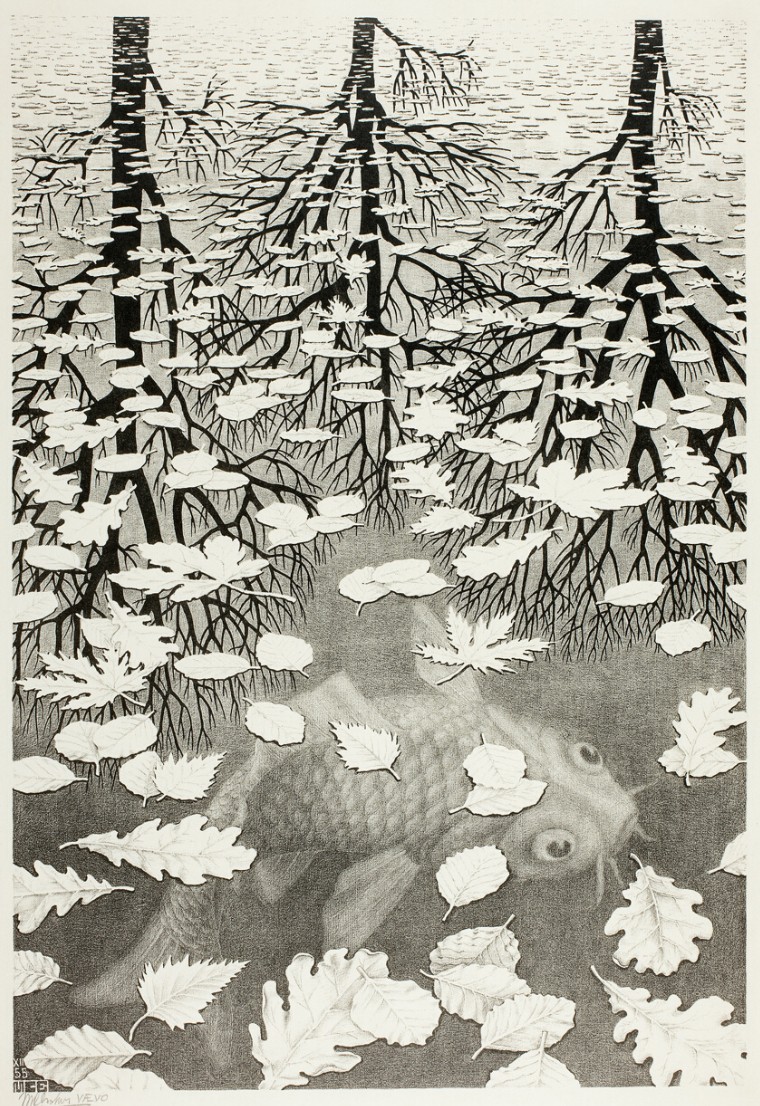

Playing with multiple levels of reality and the interaction of different spaces was one of Escher’s favorite strategies. One can see this in many of the works included in the slide show. Nature scenes like Puddle and Three Worlds draw our attention to the beautiful layering we might encounter in the natural world. Prints that are more concerned with the infinite, Mobius Strip II and Snakes draw us into never-ending lines and shapes while interpolating life-like creatures into the mathematical geometry. The interaction of two dimensional and the three dimensional forms was a primary interest of this artist and you will see it in nearly every example here. Snakes was one of Escher's most complex creations and we are fortunate that he was filmed as he worked on it. A video excerpt of this film is available on YouTube; it shows portions of each stage of production: drawing, block carving, inking, and printing.

M. C. Escher left us a treasure trove of intricately crafted picture puzzles, of which our slideshow is just a small selection. Enjoy!

Please share your comments and questions on Substack.

If the caption obscures part of the artwork, click on the image to turn off the caption.