Jean Dubuffet's Closerie Falbala

By Laura Heyrman

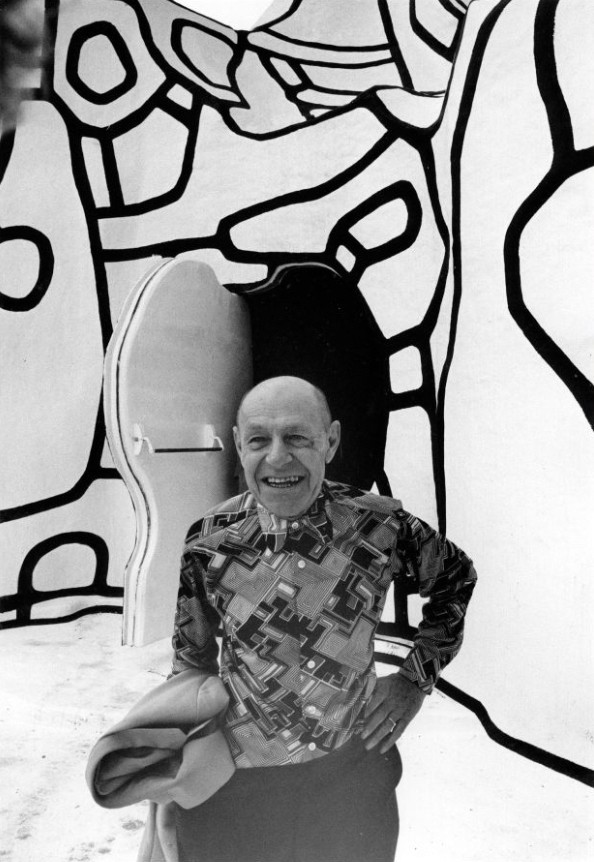

Nearly 70 years old, already famous for his highly individual paintings and sculptures, Jean Dubuffet (French, 1901 – 1985) embarked on the most strenuous project of his life. When it was completed in 1976, Closerie Falbala covered 1,925.5 square yards (1,610 square meters) with painted concrete and epoxy. The surrounding landscape was decorated with monumental sculptures and, in a nearby building, the artist’s studio, exhibition spaces, and offices for his newly created foundation were housed. Today the Fondation Dubuffet manages the property in Périgny-sur-Yerres in the southeastern suburbs of Paris; the site is open to the public by appointment.

Jean Dubuffet, the elder son of a wealthy wine merchant, was drawn to art as a young boy but painted secretly, fearful of criticism that would devalue his work in his own eyes. Still, he remained committed to art and at the age of 17, in spite of his father’s resistance to his career choice, Dubuffet enrolled in the prestigious Académie Julian in Paris. However, he found the instruction at Académie Julian pretentious and old fashioned, so he left after six months. Thereafter Dubuffet decided to create his own curriculum of reading and painting and embarked upon his artistic career. Like many artists in the early 20th century, the artist became interested in what is sometimes called Outsider Art, that is, the creative expressions of children, the incarcerated, and the mentally ill. He was especially inspired by Hans Prinzhorn’s 1922 Artistry of the Mentally Ill. Dubuffet said: “I realized that millions of possibilities of expression were available outside of the accepted cultural avenues.” The art he saw in this book rekindled Dubuffet’s insecurity about his own artistic potential and even led him to question the purpose of art generally.

Dubuffet gave up painting for 9 years as a result. He established a wine business in Paris, married, and fathered a child. He couldn’t resist his passion for art though and business success allowed the artist to set up a studio and begin painting again. He eventually delegated management of his business and returned to art full time. In spite of interruptions in his new career caused by the economic depression of the 1930s and World War Two, Dubuffet was determined to continue his artistic career. He said that he gave himself permission to “paint freely and quickly… experimenting in all directions and even preferably [rejecting] common sense.”

Dubuffet had his first solo exhibition in Paris in 1944. His work gave him a reputation as an artistic troublemaker and many viewers were shocked by his child-like drawing and his thickly applied materials, which eventually included paint as well as soil, gravel, and sand. It was at this time that Dubuffet invented the concept of Art Brut, a term he intended to refer to art by psychiatric patients, tattooists, spiritualists, self-taught artists, and incarcerated individuals. Over time though, that art has come to be known as Outsider Art, while Art Brut is usually applied to works by artists like Dubuffet who were inspired by Outsider Art.

From the 1940s on, Dubuffet worked in series, always creating art which didn’t conform to traditional ideas of beauty, reason, or logic. He experimented with natural materials like soil, wood, and butterfly wings and collected refuse from which to create sculptures. In 1960, inspired by opening a museum for his collection of Art Brut works and studying those works again, the artist embarked upon his longest lasting, most individualistic series.

"… the art that I aim for consists of developing a uniform project, an element without beginning or end, without limits or center, like the high seas." – Jean Dubuffet

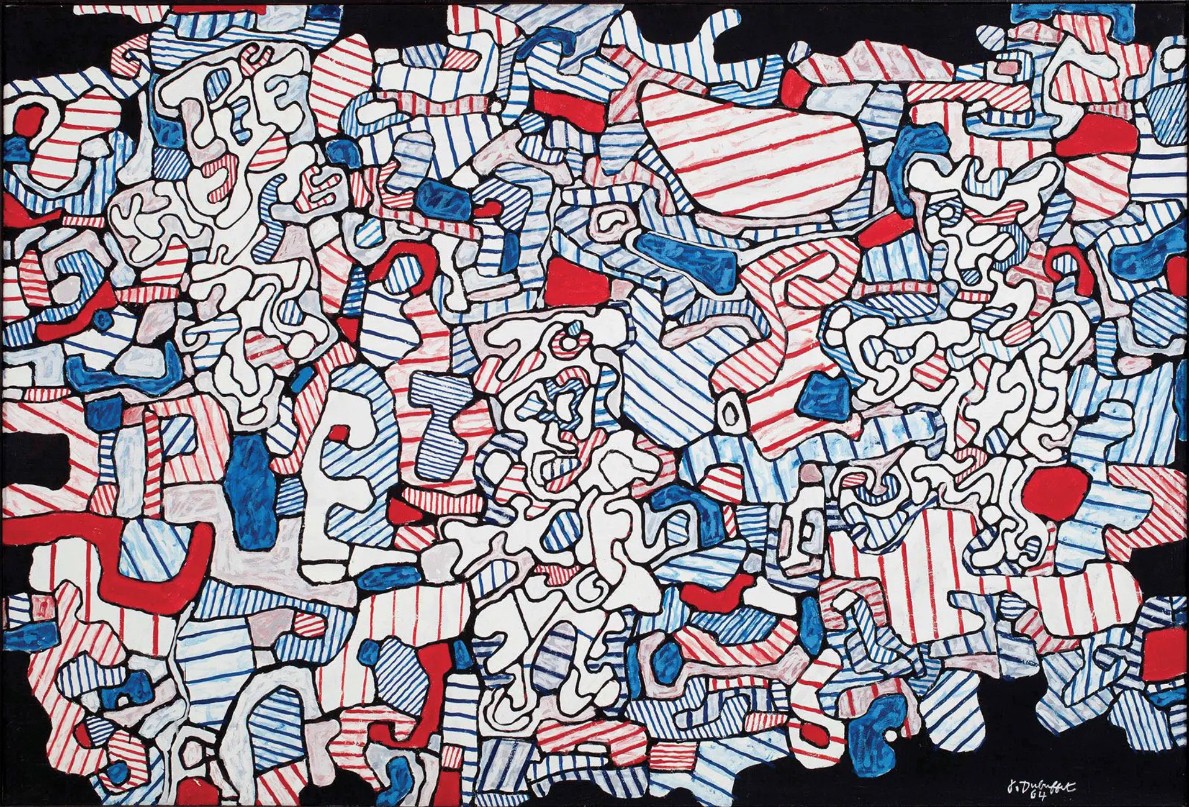

Dubuffet termed the result L’Hourloupe, an approach which occupied him for the next 12 years of his life. The artist invented the name l’Hourloupe from French words meaning to shout (hurler), to howl (hululer), and wolf (loup). The visual inspiration for the style was a doodle Dubuffet created while talking on the phone using black, red, and blue pens. He saw the doodle’s mix of shapes, colors, and patterns as the starting point from which all of the Hourloupe works could evolve – first painting, then sculpture, architecture, and even costumes and animations.

“The works connected with the Hourloupe cycle are linked closely to one another in my mind: each of them is an element intended for insertion into a whole. That whole aims to be the depiction of a world unlike ours, a world parallel to ours, if you like; and this world bears the name l’Hourloupe.” – Dubuffet

In the slide show, the painting Skedaddle (L’Escampette) demonstrates the use of L’Hourloupe in a painting. The work incorporates the usual four colors, the undulating, interconnected shapes, and contrast of patterned and solid shapes of Dubuffet’s visual language. The artist has made it almost impossible to identify figure and ground, demonstrating the interconnectedness of all things. In reproduction, L’Hourloupe works can be dizzying to look at but in person this large painting (over 4 by over 6 feet) would be more readable and what we would discern is that the open white shapes resemble three figures. Similarly shaped figures can be found in other paintings, costumes, and sculptures of the Hourloupe cycle.

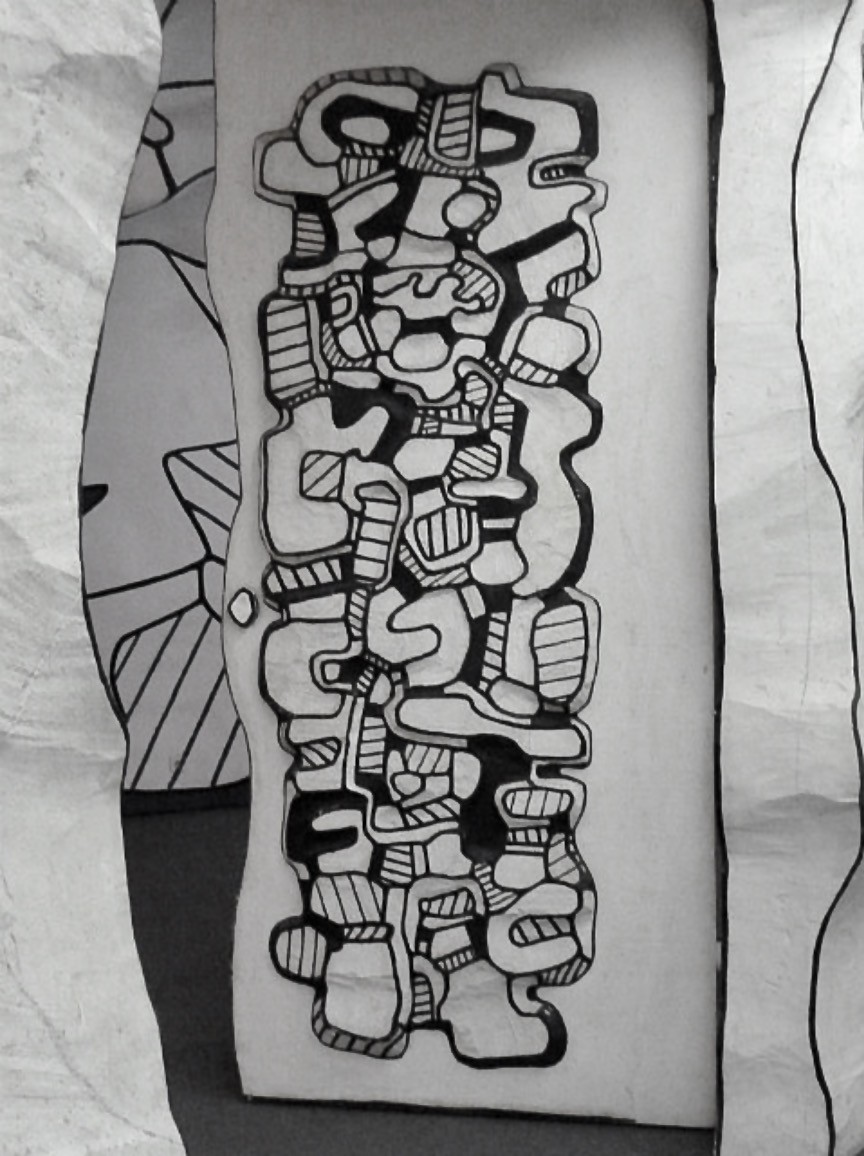

The remainder of the slide show is dedicated to the Closerie Falbala site. A “closerie” is an enclosed garden and Dubuffet’s construction begins with an imitation garden wall in white and black l’Hourloupe patterning. Outside the wall are some of Dubuffet’s monumental sculptures. The wall encloses an undulating platform with occasional bench-like protrusions, also covered in black and white patterns. Rising from the platform is a building with curving walls, rising at its highest point to over 26 feet tall (8 meters). The floor and walls were created with sprayed concrete with sculptural details added using epoxy. Polyurethane paint was used throughout. Inside, the building is divided into two areas, Antechamber (Antichambre) and Logological Cabinet (Cabinet Logologique). Housing the Cabinet was the reason Dubuffet constructed the whole site. He meant it to be a personal sanctuary where he could retreat to meditate. The Antechamber is decorated in white and blue and double doors lead to the Logological Cabinet. On the Cabinet side, the doors are decorated with raised figures in black and white, named Le Paladin and La Paladin, male and female chivalrous knights. The interior walls of the Cabinet are covered with continuous relief patterns in traditional l'Hourloupe black, red, blue, and white.

Dubuffet considered Closerie Falbala his finest work. In the decade before his death, the artist continued to execute large scale paintings, many inspired by graffiti, which attracted the admiration of younger artists including Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. As his health declined in his final months, Dubuffet worked on an autobiography and instructions on how to interpret his works. The artist died May 12, 1985.

“… we can feel on this site the feeling of no longer being in nature but in a mental interpretation thereof.” – Dubuffet

Foundation website: https://www.dubuffetfondation.com/

Video tours of Closerie Falbala by “Voyages et Passions” are available on YouTube.

Part 1: https://youtu.be/V_LQSdmsC9M?si=00_wgEnjWOs6U-RR

Part 2: https://youtu.be/aII8poQbQ1E?si=fkBDv-8nNgtgI5qC

Please share your comments and questions on Substack.

If the caption obscures part of the artwork, click on the image to turn off the caption.

Longer captions may not be fully visible on smaller screens. We apologize for the inconvenience.