Ingenuity and Creativity: Contemporary Artists and their Materials

By Laura Heyrman

My interest was captured while reading about the current exhibition “Material Matters” at Haines Gallery in San Francisco (through August 31). This exhibition features works by eight Contemporary artists whose efforts focus on using their materials in innovative ways. This prompted me to think about the role of new approaches to media in art history. In this Viewing Room, I’ve included works currently in the Haines Gallery exhibition as well as examples of other artists who share the innovative mindset explored by this exhibition.

We can trace the experimental impulse to humanity’s earliest surviving artistic efforts. Images on cave walls in Europe, Africa, and Southeast Asia, some at least 35,000 years old, show Homo sapiens using charcoal to draw, grinding colorful minerals to make paint, and experimenting with tools and even their bodies to create their images. The example in the slide show is a section of The Hall of Bulls, the largest painted space at Lascaux Cave, Montignac, France, created approximately 15,000 BCE; on a rough, pebbly surface, the painters used many colors and techniques to create the overlapping animal images. These painted figures are thirteen feet above the modern floor and would have required some form of scaffolding to execute.

Every generation of artists has shown similar ingenuity and creativity but in Modern and Contemporary art, the range of materials and technologies available has encouraged artists to achieve new modes of expression through experimentation. One of the most profound innovations of the Modern period was the invention of photography. The first practical methods of creating permanent photographic images were introduced to the public in 1839 and technical innovation progressed steadily throughout the following centuries, allowing artists to capture and manipulate virtually any image they wish, in black and white and color. In the mid-20th century, the chromogenic technique for creating color photographic prints (C-print) was introduced. C-printing became the dominant method of printing amateur and professional color photographs. As color photography began to be accepted among fine art photographers and collectors in the 1970s, the C-print process became a preferred technique. An example of an early fine art C-print by Ernst Haas (Austrian-American, 1921-1986) is included below.

Contemporary photographer Matthew Brandt (American, b. 1982), one of the artists in the Haines exhibition, employs various traditional photographic printing techniques in decidedly non-traditional ways. In many works, he first creates a traditional C-print from a photograph he has taken. Brant then alters and distorts the printed image by manipulating it in a manner inspired by the subject of the photograph. In the example below depicting the Vatnajökull glacier in Iceland, the photograph was altered with heat and water, inspired by Iceland’s volcanic and glaciated landscape.

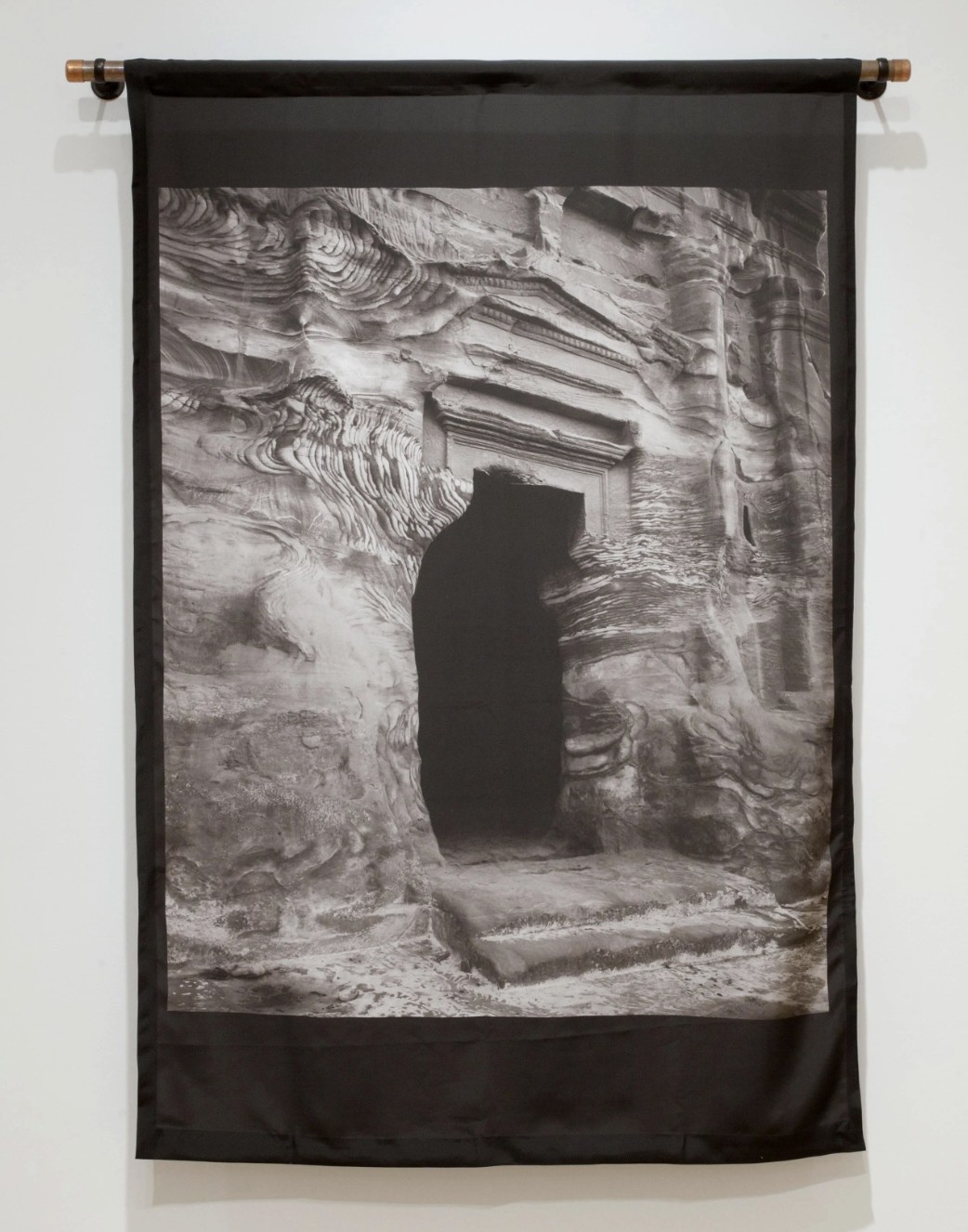

A second photographer included in the “Material Matters” exhibition is Linda Connor (American, b. 1944). Long interested in sites with spiritual connections, Connor has traveled the world photographing the interaction of the manmade with the natural landscape, usually choosing places with a history of ritual or contemplative use. For many years, Connor's works were traditionally printed and published in books but in the last two decades, she has begun reprinting images on unconventional supports like aluminum and silk.

Though less momentous in its impact than the invention of photography, paint media and application have also seen innovations between the 19th century and the present. It was in the 19th century that painters began to move out-of-doors to work, first with watercolors but then with oil paint. The Impressionists and their contemporaries were able to shift to plein air (outdoor) painting because of the invention of portable easels and especially, the invention of paint in foil tubes. With these developments, artists could carry their canvases about and capture the world as they saw it in the moment. Oil paint, a versatile innovation of the 15th century, saw its supremacy challenged in the 20th century by the invention of a variety of synthetic paints. First used as house paint (familiar to us as latex paint), artists soon began to experiment with acrylic polymer paints. Though many painters still use oil paint, acrylics have many appealing qualities; they are water-based, can be applied to imitate other media including watercolor and oil paint, and they are quick drying. Morris Louis (American, 1912-1962) was one of the artists who explored the possibilities of acrylic and other synthetic paints, usually applying extremely diluted paint to unprimed and unstretched canvas, as in Beth Chaf of 1959.

The only traditional painter included in the Haines Gallery exhibition, Berkeley, California-based David Simpson (American, b. 1928) continues the Color Field tradition of which Louis was a founder. Simpson has worked in three consecutive styles, landscape-derived horizontally striped abstractions (1955-1963), geometric abstractions where vivid squares of various sizes are ranged around the edges of colorful canvases (late 1970s-late 1980s) and single colored panels using interference paints which contain titanium oxide (since the late 1980s). Such paints provide shimmering light interactions; Interference Triple (1991) in the slide show is an example.

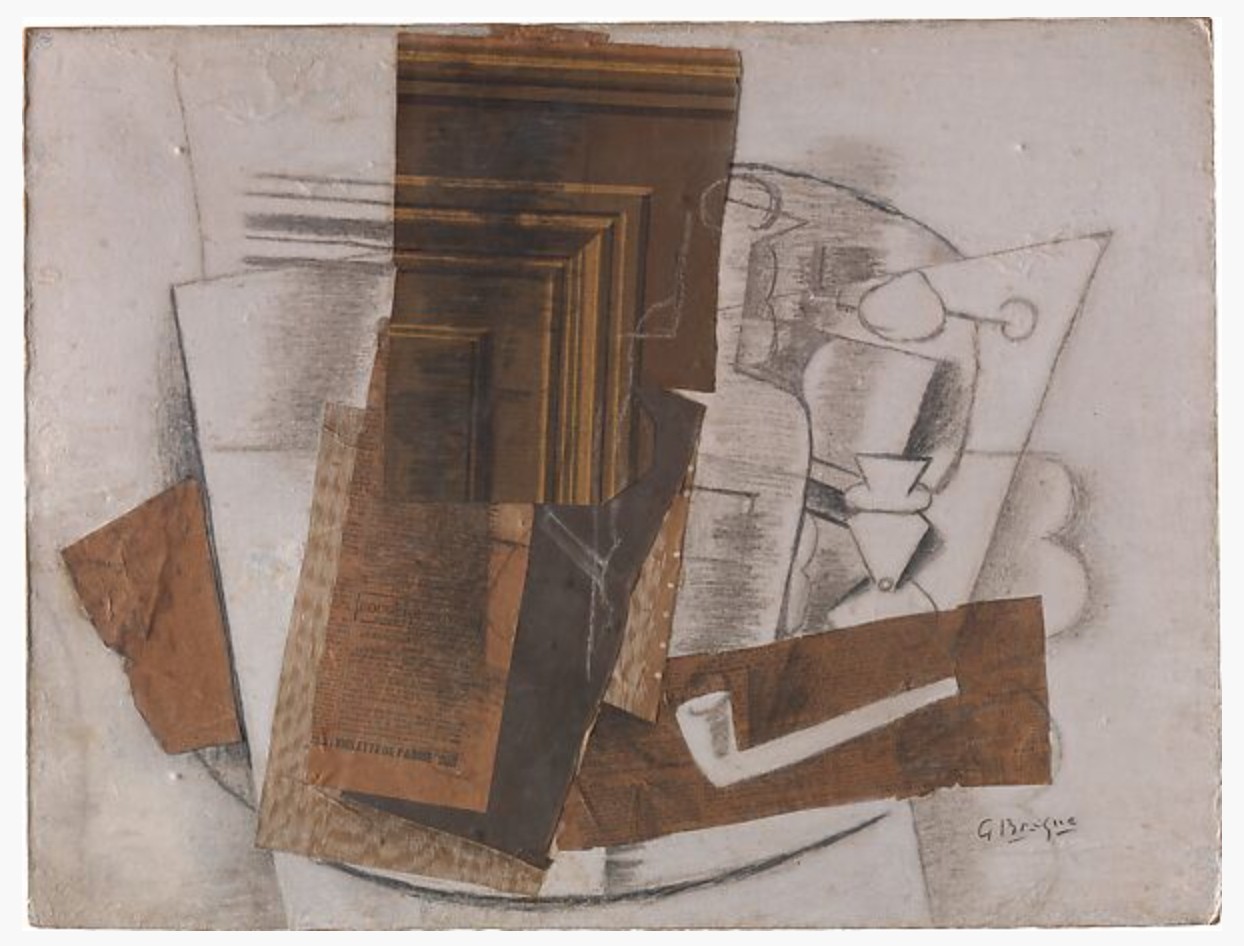

The introduction of collage (a combination of pasted, usually flat materials to create an image or design) was an important innovation in the creation of two-dimensional imagery in the early 20th century. Though 18th and 19th century women had used a type of collage as a means of self-expression in home décor and photo albums, the idea of collage as a component of the fine arts did not appear until the rise of Cubism. Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) and Georges Braque (French, 1882-1963) began cutting apart various printed papers and reassembling them to create images. For the Cubists, collage was a short cut to reimagining reality in a fragmented form, an idea central to the movement. An example by Braque is included in the slide show.

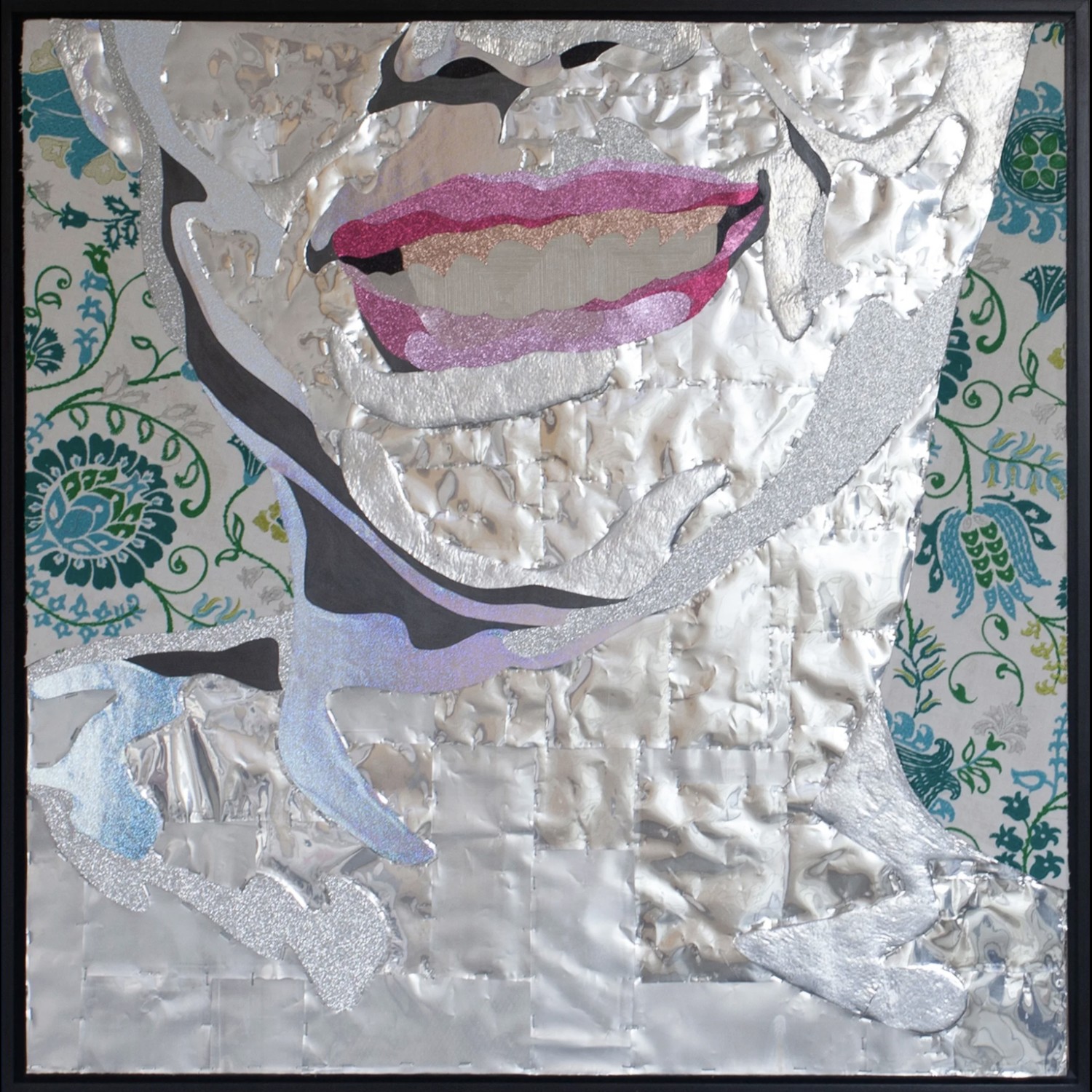

Since it was introduced, collage has served artists with a wide variety of artistic goals. Three of the artists in “Material Matters” can be considered to be working in collage-related techniques. The most traditional collagist is Stuart Robertson (Jamaican-American, b. 1992). He creates images of Black people and their lives, taken from family albums, archives, and social media. He uses a wide variety of materials: bubble wrap, papers, fabrics, and especially metallic elements, including aluminum cans. The artist has said “These lustrous figures offer unusual interactions with images of Blackness and invoke metaphors of skin colour that position skin as much more than an indicator of race.”

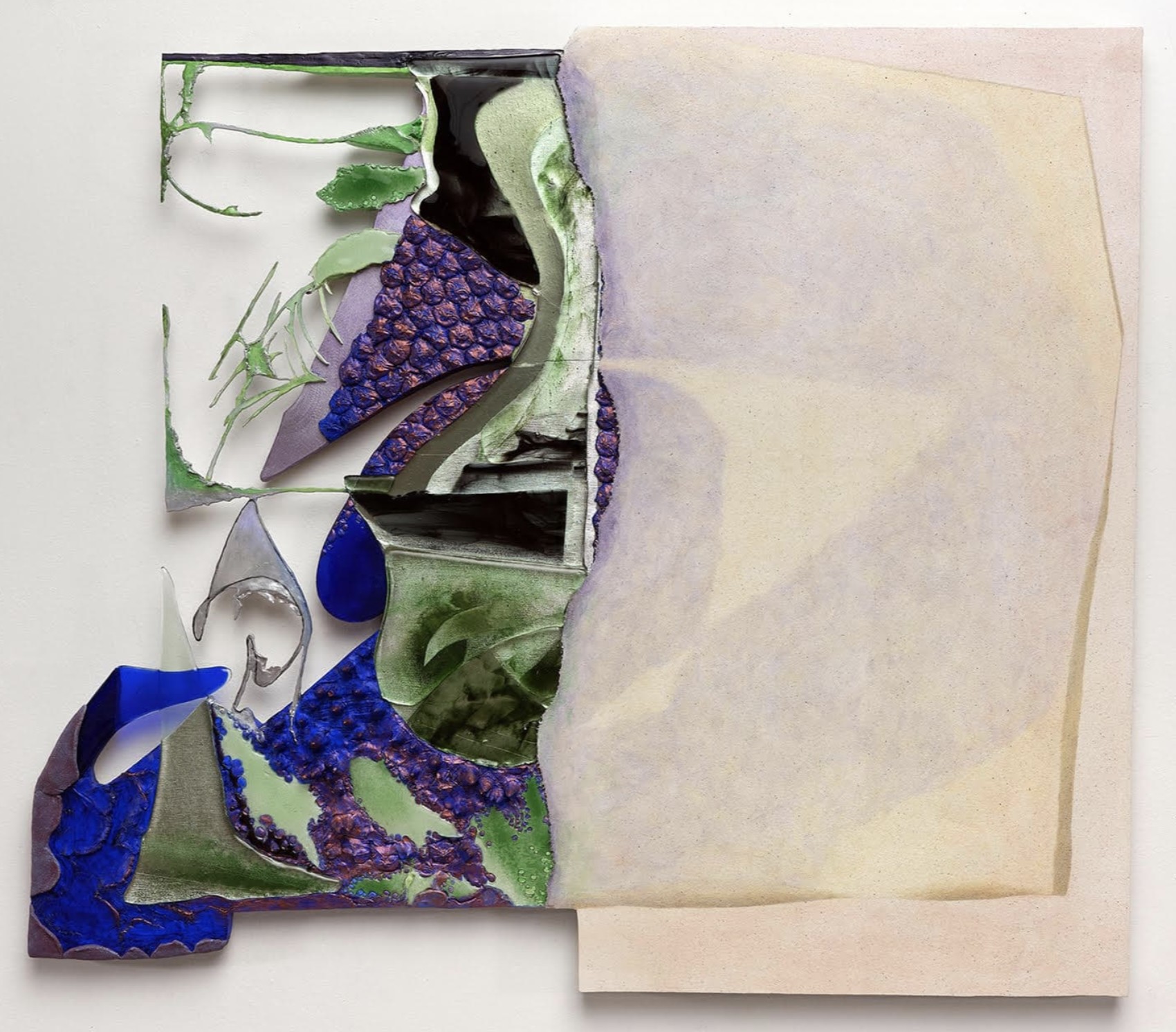

Though Leslie Shows (American, b. 1977) doesn’t use much paper as has been traditional in collage, her works have the visual impact of collage with their layered and varied materials, colors, and textures. Ferryman (2022) incorporates glass and sand, acrylic paint and ink, canvas, resin, and plaster, and steel and aluminum. The artist plans out her compositions through a long process that includes collecting found images, growing some of her materials, such as rust and salt crystals, and creating strips of color by applying acrylic paint to Plexiglass and peeling it off in reusable strips. The colors and shapes suggest representation and narrative but their abstraction and overlapping force the viewer to decipher the work from ambiguous clues.

Sculptor Deborah Butterfield (American, b. 1949) creates assemblages, the three-dimensional counterpart to two-dimensional collage. When the artist settled on the horse as her particular theme, she began by making works from found objects and materials. Eventually she developed a method of casting her found materials in bronze; she would then paint or otherwise treat the cast bronze so that it would look just like the original material. Two Seas (2023-2024), included in the exhibition at Haines Gallery, shows this, with illusionistically painted bronze depicting driftwood as the main components of the horse’s body, and painted bronze representations of ocean flotsam and jetsam: knotted rope, a piece of torn fishing net, part of a buoy, and pieces of plastic refuse. The illusionism of Butterfield’s sculptures is impressive, and frequently deceives viewers of her works, even after close looking.

Two Chinese sculptors round out the group of artists in the exhibition “Material Matters,” Ai Weiwei (b. 1957, lives and works in Portugal) and Zhan Wang (b. 1962). Both artists are known for depicting objects in unexpected materials. Ai’s Handcuffs from 2012 are an accurate representation of the title object, though carved from a type of wood usually used for creating fine furniture. In contrast to Butterfield, Ai made no effort to disguise his material and the incongruity of object and material is part of the meaning of the work. Zhan Wang’s sculptures use modern, industrial materials to create large scale objects that imitate the appearance of a traditional Chinese object, the scholar’s rock or gongshi. Usually pieces of eroded limestone, scholar’s rocks ranged in size from less than a pound to hundreds of pounds. The small ones were intended for indoor display while the large ones were focal points of traditional gardens. Zhan’s bright stainless steel sculptures have an industrial shininess which contrasts strongly with the texture of natural limestone.

The diversity of materials available to present day artists means that creative experimentation will continue unabated. If a substance exists in the world, chances are that an artist somewhere is playing around with it and seeking a practical means of incorporating it into innovative art. For artists and those of us who enjoy their creations, that can only lead to exciting results.

“Material Matters” continues at Haines Gallery, 2 Marina Boulevard, Building C, San Francisco, California, through August 31, 2024. hainesgallery.com/exhibitions/86-material-matters

Please share your comments and questions on Substack. irequireart.substack.com/p/viewing-room-24/comments

Longer captions will not be fully visible on smaller screens. We apologize for the inconvenience.

When the caption obscures part of the artwork, click on the image to turn off the caption.